Key Takeaways

- It Didn’t Start with H.G. Wells: While Wells mechanized the process, the concept of time dilation and relativity exists in Hindu mythology (The Mahabharata), Japanese folklore (Urashima Tarō), and Irish Legend (Tír na nÓg) dating back thousands of years.

- Magic Needs Rules (Or It Sucks): The most effective fantasy time travel adheres to strict mechanical constraints—whether it’s the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle seen in Harry Potter’s Time-Turners or the “gemstone capacitor” requirements of Outlander.

- The “Erase” Button is Dangerous: Robert Jordan’s Balefire in The Wheel of Time introduces retroactive causality, a high-risk narrative device that threatens the fabric of the universe (and the plot) if used without consequence.

- Physics is Fantasy’s Best Friend: Concepts like Closed Timelike Curves (CTCs) and gravitational time dilation provide a “hard magic” framework that grounds high fantasy, making the impossible feel plausible.

- The “Mentor Your Past Self” Trope: Terry Pratchett’s Night Watch deconstructs the glamour of time travel, focusing on the gritty emotional labor of teaching your younger, stupider self how to survive.

- The Theology of Stasis: The legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus introduces the concept of “preservation via stasis” rather than active travel, bridging the gap between divine intervention and temporal displacement.

1. The Ancients Knew Relativity Before Einstein: Mythology and Folklore

Let’s dispel a common myth right out of the gate: H.G. Wells did not invent time travel. He just put a steering wheel on it. Long before Victorian gentlemen were tinkering with brass gears and quartz rods, ancient cultures were grappling with the terrifying fluidity of time. They didn’t call it “General Relativity,” but they understood the core concept: Time is not a constant; it is a variable dependent on where you are and who you are hanging out with.

The arrogance of the modern sci-fi enthusiast often overlooks the deep, structural understanding of temporal mechanics found in oral traditions. These weren’t just “magic stories”; they were sophisticated explorations of entropy, loss, and the relative nature of human experience against the backdrop of the divine or the fae.

1.1 Hindu Cosmology: The Scale of Deep Time and Gravitational Dilation

If you want to feel insignificant, read the Puranas. Western sci-fi gets excited about jumping back a few decades to kill Hitler or buy Apple stock. Hindu mythology operates on a scale that makes deep space look like a backyard puddle. The ancient seers of India didn’t just stumble upon the idea that time moves differently for gods; they codified it into a mathematical system that eerily parallels modern astrophysics.

The seminal text here is the story of King Kakudmi and his daughter Revati, found in the Mahabharata and the Vishnu Purana. Kakudmi, a powerful ruler of Kushasthali, was looking for a husband for Revati. Revati wasn’t just royalty; she was virtuous, accomplished, and beautiful—so much so that Kakudmi, being a bit of a perfectionist (and a helicopter parent), decided no mortal man was good enough. He needed a recommendation from the top. So, he took his daughter to Brahmaloka, the abode of Lord Brahma, the Creator.

The journey itself implies a transit through different planes of reality, a common trope in fantasy that suggests “distance” is not just spatial but temporal. When they arrived, Brahma was busy listening to a musical performance by celestial Gandharvas. Kakudmi, being polite and understanding court protocol, waited. It felt like perhaps an hour or so—maybe the length of a decent album or a short concert. When the music stopped and Kakudmi presented his shortlist of suitors, Brahma laughed.

“O King, all those whom you may have decided within the core of your heart to accept as your son-in-law have died and passed away. Their sons and grandsons and even their great-grandsons are no more.”

Brahma explains that time runs differently on different planes of existence. While Kakudmi waited for a “few moments” in the gravitational heavy-lifting zone of the Creator, 27 Chatur-Yugas (cycles of four ages) had passed on Earth. We are talking about millions of years. The suitors were dust. The kingdoms were gone. Humans were physically shorter and intellectually dimmer than when Kakudmi left.

Technical Insight: Gravitational Time Dilation This is arguably the earliest recorded instance of Gravitational Time Dilation. In modern physics, as per Einstein’s General Relativity, time passes slower closer to a massive gravitational object (or energy source). Brahma’s realm, being the center of creation, acts as the massive object. The sheer “weight” of the divine presence warps spacetime. This is exactly the plot of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (Miller’s Planet), where one hour equals seven years, but written nearly 2,500 years earlier.

The text even accounts for biological and evolutionary drift. When Kakudmi returns, he finds that humans have devolved; they are shorter and possess less vitality. This forces a physical adaptation: Balarama, Revati’s new husband (and brother of Krishna), has to use his plow to physically “shorten” Revati to match the current epoch’s stature. It is a bizarre, visceral detail that grounds the high concept in physical reality.

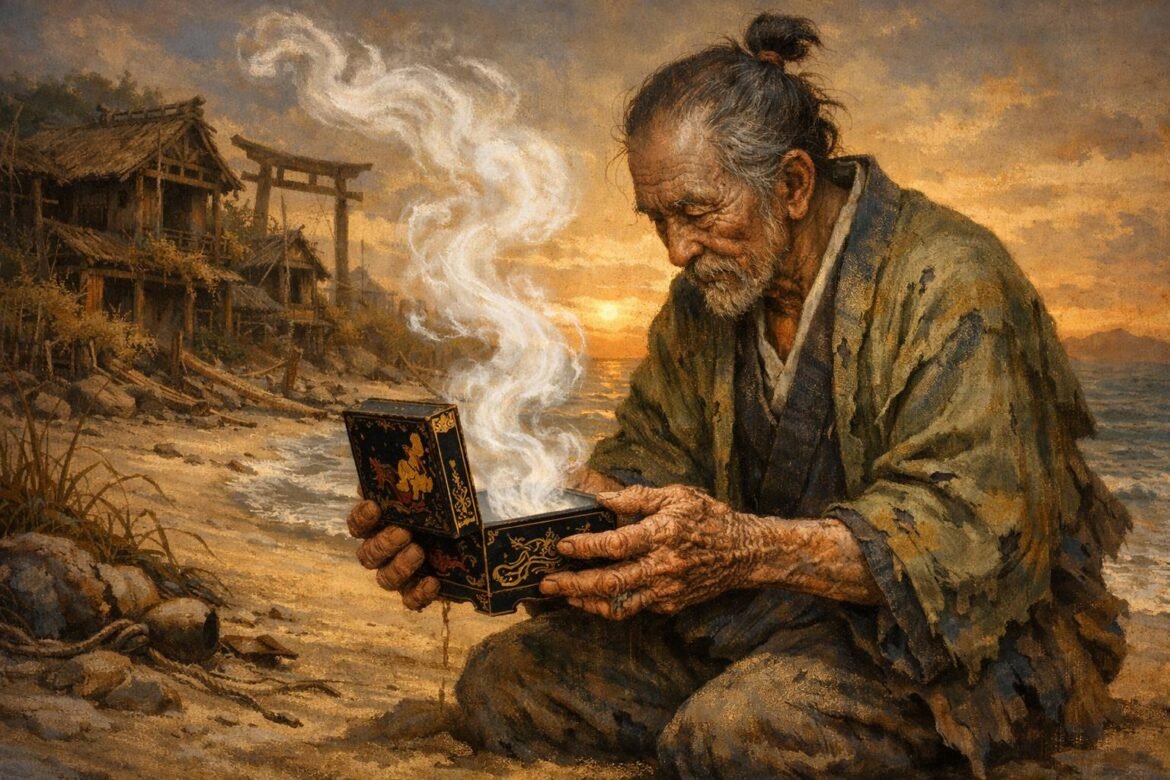

1.2 The Japanese “Rip Van Winkle”: Urashima Tarō and Entropy Boxes

Moving from the cosmic to the folkloric, we hit Japan and the tale of Urashima Tarō. This isn’t about gods laughing at mortals; it’s about the tragedy of lost time and the physical cost of cheating entropy.

Urashima, a fisherman, saves a turtle and is rewarded with a trip to Ryūgū-jō, the Dragon Palace under the sea. He spends what he thinks is three days feasting and partying with a princess. The “undersea” realm functions similarly to the Fae Wilds in Western mythology—a place of stasis and pleasure. When he gets homesick and returns to the surface, he finds his village gone, his family dead, and 300 to 700 years having passed (depending on the version).

The kicker—and the part that makes this a masterclass in fantasy writing—is the mechanic of the box. The princess gives him a tamatebako (jeweled box) and tells him never to open it. Of course, stricken with grief and confusion, he opens it. A wisp of white smoke comes out, and Urashima instantly ages those hundreds of years, turning into a withered crane or dust.

Literary Analysis: The Containment of Entropy The box contains his “time.” It’s a physical manifestation of the years he skipped. This introduces a fascinating trope: Time Debt. You can borrow time, you can skip it, but eventually, the debt must be paid. The box acts as a Faraday cage for entropy. As long as it is sealed, Urashima exists in a superposition of “young” and “ancient.” Breaking the seal collapses the waveform. In fantasy writing, this is a powerful check on power. If you travel, you lose something. It prevents the protagonist from acting with impunity.

1.3 The Celtic “Do Not Touch the Floor” Rule: Grounding Wires

In Irish mythology, we have Tír na nÓg (The Land of Eternal Youth). The hero Oisín is whisked away by Niamh of the Golden Hair. He spends three years there, but like Kakudmi, he gets homesick. Niamh lends him her white horse, Embarr, to visit Ireland but gives him a specific technical instruction: Do not dismount. If his feet touch the soil of Ireland, he can never return.

Oisín finds Ireland changed. The chaotic, heroic pagan Ireland he knew is gone, replaced by the ordered, Christian Ireland of St. Patrick. The men are smaller, weaker. When Oisín leans down to help some weaklings move a stone, his saddle strap breaks. He hits the ground. Instantly, the 300 years he “skipped” catch up. He turns into a withered, blind old man.

The Mechanic: Planar Grounding This introduces the concept of Planar Grounding. The magic that sustains his youth is insulated by the horse (a conduit of Tír na nÓg). The “earth” of the mortal world acts as a grounding wire, discharging the magic and reasserting the laws of linear entropy. It’s a brilliant limitation for a magic system: You can observe the past/future, but you cannot integrate with it without consequence.

1.4 The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus: Biological Stasis vs. Travel

While the previous examples involve moving between realms (Space-Time travel), the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus introduces time travel via stasis. Found in both Christian and Islamic traditions (Surah Al-Kahf in the Quran), the story concerns a group of youths hiding from religious persecution (under Decius, around 250 AD) in a cave.

They pray to be saved, and God puts them to sleep. They wake up some 200–300 years later (during the reign of Theodosius II), believing they have only slept for a day. They send one of their number to buy food, and the copper coins he uses—bearing the face of Decius—reveal the anomaly.

The “Forward-Only” Trip This is essentially “Cryogenic Suspension” via divine intervention. It highlights a critical distinction in time travel tropes: Subjective vs. Objective Time. For the sleepers, subjective time was one night; objective time was centuries. Unlike Kakudmi or Oisín, there is no magical realm involved—just a suspension of biological processes in the “real” world. This trope is the ancestor of sci-fi plots like Planet of the Apes or Aliens, but in a fantasy context, it serves to turn the characters into living artifacts, relics of a past age forced to confront a future that views them as saints or curiosities.

1.5 Native American Folklore: The Enchanted Moccasins

Less commonly cited but equally fascinating is the Native American tale of the “Enchanted Moccasins”. A boy, Ko-ko, is given magical moccasins by his grandmother to travel to distant lands. The moccasins possess a form of speed/teleportation, but the narrative plays with the perception of time and distance. While not a direct “time machine” story in the Wellsian sense, the manipulation of space often correlates to the manipulation of time in folklore (as seen in the “seven-league boots” trope).

In some versions, the protagonist returns to find that what felt like a journey of days has consumed years of life elsewhere. This reinforces the universal human anxiety regarding travel: that to leave one’s place is to leave one’s time, and the home you return to is never the home you left.

| Myth/Legend | Mechanism of Travel | The Consequence | Modern Equivalent |

| King Kakudmi (Hindu) | Gravitational Dilation (Brahma’s Realm) | Loss of era, family, and cultural stature | Interstellar (Black Hole Dilation) |

| Urashima Tarō (Japan) | Fae Realm Stasis (Dragon Palace) | Rapid aging upon opening a containment object | In Time (Time as currency/debt) |

| Oisín (Celtic) | Planar Insulation (The White Horse) | Instant entropy upon touching “mortal” soil | Grounding electrical current |

| Seven Sleepers (Christian/Islam) | Divine Stasis (Sleep) | Displaced out of time, cultural alienation | Cryogenics / Futurama |

2. The “Oops” Era: Early Modern Time Travel (Pre-Wells)

Before the “Time Machine” became a machine, it was usually a dream, a ghost, or a very hard knock on the head. The industrial revolution hadn’t quite convinced everyone that we could build our way out of the fourth dimension yet, so the mechanisms were often spiritual or satirical.

2.1 The First “Documented” Time Travel: Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733)

Most people haven’t heard of Samuel Madden’s 1733 book, Memoirs of the Twentieth Century, but it is technically the first time-travel narrative in English literature.

The premise is wild and distinctly non-mechanical: A guardian angel delivers a series of letters to the author from the years 1997 and 1998. It isn’t a machine; it is a divine courier service. The book was a satire of the 18th century, using the “future” to mock the present—a tradition that Star Trek and Black Mirror would continue centuries later.

The Satirical Device Madden wasn’t interested in the physics of 1998; he was interested in the politics of 1733. By projecting current trends (specifically the dominance of Jesuits and geopolitical shifts) to ridiculous extremes, he used time travel as a mirror. Interestingly, Madden destroyed most copies of the book shortly after publication. Perhaps he realized that writing about the future is a great way to look foolish when the future actually arrives, or maybe the political heat was too much. Regardless, it established the Epistolary Time Travel format—information sent back, rather than people.

2.2 Dickens and the Ghosts of Causality: A Christmas Carol

Is A Christmas Carol (1843) a time travel story? Absolutely. It is arguably the most famous time travel story in existence, often miscategorized as a simple ghost story.

Scrooge doesn’t just “remember” the past; he travels there. The Ghost of Christmas Past takes him to a physical location where he sees his younger self. He cannot interact—he is an invisible observer—but the journey serves a functional purpose: Data Retrieval. Scrooge retrieves emotional data (regret, joy, loss) that he had deleted from his active memory to survive his trauma.

The Conditional Future The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come creates a Conditional Future or a Probabilistic Simulation.

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead… but if the courses be departed from, the ends will change.”

This is the Many-Worlds Interpretation (or at least a branching timeline theory) in Victorian drag. Scrooge changes the present to erase the future he saw. He collapses the waveform of the future into a new reality where Tiny Tim lives. Unlike the Novikov Principle (where the future is fixed), Dickens argues for Free Will within a temporal framework. The future is a shadow, not a stone.

2.3 Twain’s Blunt Force Trauma: A Connecticut Yankee

Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) introduces the “Isekai” (portal fantasy) trope via traumatic brain injury. Hank Morgan, a 19th-century engineer, gets hit with a crowbar and wakes up in 528 AD.

Twain didn’t care about the how. He cared about the what. This is the “Engineer’s Fantasy”—the idea that modern technical knowledge is a form of magic. Hank predicts a solar eclipse (using knowledge he memorized) to threaten the King, effectively weaponizing astronomy.

The Storyteller’s Lesson: Knowledge as Power Twain’s approach is valid for writers who hate technobabble. You don’t always need a flux capacitor; sometimes you just need a crowbar. The mechanism is secondary to the juxtaposition of eras. However, Twain’s ending is bleak. Hank introduces modern warfare (Gatling guns, electricity) to Arthurian legend and ends up destroying the chivalric world, trapped by the rotting bodies of the knights he slaughtered. It’s a cautionary tale: Technological superiority does not equal moral superiority.

3. The Mechanics of Modern Fantasy: Hard Magic vs. Hand-Waving

Now we get to the meat of the report. How do the heavy hitters of modern fantasy handle the temporal mess? The best systems are those that impose strict costs and limitations.

3.1 Harry Potter and the Closed Loop (The Novikov Principle)

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban provides one of the cleanest literary examples of a Closed Timelike Curve (CTC) adhering to the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle.

The Novikov Principle states that if an event exists that would cause a paradox or any change to the past whatsoever, the probability of that event is zero. In short: You cannot change the past; you can only fulfill it.

In the book, Harry is saved from the Dementors by a mysterious figure he thinks is his father. Later, after using Hermione’s Time-Turner, he realizes he was the one who cast the Patronus. He had to go back to save himself because he had already been saved by himself.

“I knew I could do it this time,” said Harry, “because I’d already done it… Does that make sense?”

The Inscription and the Limit The Time-Turner itself is inscribed with a warning:

“I mark the hours, every one, Nor have I yet outrun the Sun. My use and value, unto you, Are gauged by what you have to do.”

Rowling (or her editors) realized this mechanic was too powerful. If you can fix anything, death loses its sting. This is why the lore establishes a “safe limit” of about five hours. Go back further, and you risk “catastrophic harm to the witch or wizard or time itself.” This is why they couldn’t just go back and kill baby Voldemort. The limitation saves the plot. The eventual destruction of the entire stock of Time-Turners in Order of the Phoenix was a necessary narrative purge to return stakes to the story.

3.2 Outlander: Gemstones, Blood, and Geodesy

Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series moves time travel from “mental exercise” to “visceral physical trauma.” It treats time travel almost like radiation poisoning or deep-sea diving—a physical hazard that requires protection.

The Mechanism of the Stones

- Fixed Locations: Standing stones (Craigh na Dun) located on ley lines or geomagnetic anomalies. The buzzing sound characters hear is a brilliant touch—it mimics infrasound or the “hum” often reported near high-voltage equipment, suggesting a bleed-through of energy.

- Genetic Component: Not everyone can travel. It’s a hereditary trait (the “traveler gene”). This makes it exclusive, a “chosen one” mechanic that feels biological rather than mystical.

- The Capacitor (Gemstones): Gemstones are required to steer and protect the traveler. They act as capacitors, absorbing the chaotic energy of the transition. Often, the gems disintegrate upon arrival. This gives travel a literal financial cost. You can’t just pop back and forth; you need diamonds.

- Blood Sacrifice: While not strictly necessary for Claire, other characters (like Geillis Duncan) believe blood sacrifice is required. This adds a layer of folk magic/ritualism—the belief that life pays for life.

Fixed vs. Flexible Timelines Outlander plays with a mix of “Fixed” and “Flexible.” They try to stop the Battle of Culloden. They fail. The history books were right. This suggests a Self-Correcting Timeline or Elastic History. You can make small ripples (save a person here or there), but the river of history is too wide and the current too strong to divert completely. This creates “Tragic Irony,” a delicious flavor for any fantasy novel.

3.3 The Wheel of Time: Balefire and Retroactive Erasure

Robert Jordan didn’t just include time travel; he included Time Deletion. This is one of the most unique and dangerous mechanics in fantasy.

Balefire is a weave of the One Power that burns a thread out of the Pattern. If you hit someone with Balefire, they don’t just die now; they died minutes or hours ago, depending on the amount of power used.

“A bar of white light that made noonday sun seem dark…”

The Consequence: The Pattern Unravels If you Balefire a Darkhound that just ate your friend, the Darkhound died before it ate your friend. Your friend comes back to life. This sounds like a cheat code, but Jordan added a cosmic cost: The Pattern Unravels. Reality is a tapestry. If you keep pulling threads out retroactively, the fabric weakens. Cracks form in reality. People start seeing double visions; geometry fails; the ground turns to glass or mist.

This forces a moral dilemma: Efficiency vs. Existence. The heroes can save the day with Balefire, but if they do it too much, they destroy the universe they are trying to save. It is a nuclear deterrent metaphor wrapped in high fantasy magic.

3.4 Discworld: The “Twerp” Theory of Mentorship

Terry Pratchett’s Night Watch is arguably the best “time travel” novel in fantasy because it rejects the glamour entirely. Pratchett uses time travel not to fix the world, but to fix the man.

Sam Vimes is sent back 30 years. He doesn’t meet famous historical figures to ask for autographs; he meets his own mentors and his younger self. He has to take on the role of John Keel, the man who taught him how to be a good cop.

The Insight: You Are Not Your Hero Vimes realizes his younger self wasn’t a hero in the making; he was a “twerp.”

“But when you got older you found out that you NOW wasn’t YOU then. You then was a twerp.”

Pratchett uses time travel to explore Character Growth rather than plot mechanics. Vimes has to parent himself, teaching young Sam the hard lessons, knowing that he (Vimes) is suffering through the trauma a second time so that young Sam can survive it the first time. It is gritty, cynical, and deeply human. It posits that we are the sum of our traumas, and to erase them is to erase ourselves.

4. The Physics of the Impossible: Making Magic Sound Smart

You want your magic system to hold up to scrutiny? Steal from physics. You don’t need to explain the math, but using the concepts adds weight.

4.1 Closed Timelike Curves (CTCs) and General Relativity

In General Relativity, a CTC is a worldline of a particle that returns to its starting point in spacetime.

- The Concept: Einstein’s field equations allow for solutions where time loops back on itself. Gödel discovered this in 1949.

- Fantasy Application: This is your Time-Turner. The future has already affected the past. This is excellent for “Prophecy” stories. The prophecy isn’t predicting the future; it’s a memory from a CTC. The information exists in a loop with no clear origin (The Bootstrap Paradox).

4.2 Entropy and the Arrow of Time

The Second Law of Thermodynamics says entropy (disorder) always increases. Time moves forward because you can’t unscramble an egg.

- Fantasy Application: If a wizard travels back in time, they are fighting the universal flow of entropy. This should generate Heat. Lots of it. Outlander uses this—the stones feel hot, the gems burn up. Magic shouldn’t be free; it should generate waste heat. If you reverse time in a localized area (like Doctor Strange with the apple), the energy required to reverse entropy should be staggering.

4.3 The Many-Worlds Interpretation (MWI)

Quantum mechanics suggests that every decision creates a branching universe.

- Fantasy Application: This is the “Zelda” or “Trunks” (DBZ) timeline. If you go back and kill the Dark Lord, you create a new timeline where he is dead, but your original timeline (where he killed your parents) still exists. You can never truly “fix” your home; you can only become a refugee in a better timeline. This is tragic and melancholic, perfect for grimdark fantasy.

| Physics Concept | Fantasy Equivalent | Narrative Effect |

| Gravitational Time Dilation | Fae Realms / Brahmaloka | “Rip Van Winkle” effect; protagonist outlives everyone. |

| Closed Timelike Curve | Time-Turner / Prophecy | Fixed Loop; implies destiny/fate is absolute. |

| Quantum Superposition | Divination / Seeing Futures | The future changes based on observation (Scrooge). |

| Entropy Reversal | Healing / Balefire | High energy cost; reality degradation. |

5. The Storyteller’s Perspective: How to Write This Without Ruining Your Book

As a copywriter and narrative analyst, I see writers paint themselves into corners constantly. Time travel is a narrative nuke. If you drop it in act three without setup, you haven’t written a twist; you’ve written a cop-out. Here is the pragmatic advice on handling time travel.

5.1 Define Your Paradigm Early (And Stick to It)

There are only three options. Pick one.

- The Fixed Loop (Harry Potter): You can’t change anything. The travel is for information or fulfilling a loop. Pro: High structural integrity. Con: Low stakes (the outcome is guaranteed).

- The Multiverse (Marvel/Zelda): Changing the past creates a branch. Pro: Infinite creative freedom. Con: Emotional stakes are lowered because “nothing matters” if you can just hop to a new reality.

- The Elastic Timeline (Outlander/11.22.63): You can change things, but time “pushes back.” Small changes heal; big changes require massive sacrifice. Best for: Drama and suspense.

5.2 The “Sanderson’s First Law” of Time Travel

Brandon Sanderson’s First Law of Magic states: An author’s ability to solve conflict with magic is directly proportional to how well the reader understands said magic.

If your hero uses time travel to solve the climax, the reader must understand the rules and costs 200 pages earlier. If the Time-Turner appears in the last chapter to fix the death of the main character, that is not a plot twist; that is a Deus Ex Machina, and your readers will hate you.

- Bad: “Oh, I have this amulet that reverses time! I forgot to mention it!”

- Good: The hero spends the whole book gathering gemstones for the spell, knowing it will cost them their life (Outlander style).

5.3 Limit the Resource (The Nerf)

Time travel is the ultimate power. You must nerf it immediately.

- Cost: It requires rare gems (Outlander) or life force.

- Damage: It unravels reality (Wheel of Time).

- Sanity: It breaks the human mind to see the eons pass (The Jaunt/Lovecraftian tropes).

- Bureaucracy: There are Time Police (Discworld’s History Monks or the TVA). The “Monks of History” in Discworld ensure that time happens in the right order, moving time from places where it is not needed (underwater) to places where it is (cities).

5.4 Avoid the “Hitler Paradox”

Why don’t they go back and kill the villain as a baby? You need a reason.

- The “Voldemort Rule”: The villain was too well guarded/hidden even then.

- The “Fixed Point” Rule: If you kill him, someone worse rises (The Power Vacuum theory).

- The “Bootstrap” Rule: You tried, but your attempt to kill him is exactly what gave him the scar/motivation to become the villain.

5.5 Focus on the Human Element

The best time travel stories aren’t about the date; they are about the people.

- Regret: Time travel is the ultimate metaphor for regret. “If I knew then what I know now.”

- Alienation: The traveler is always an immigrant in time. They don’t speak the language; they don’t know the customs.

- Love: Love across time (The Time Traveler’s Wife, Outlander) emphasizes the endurance of connection against the entropy of the universe.

6. FAQ (Schema.org Optimized)

Q: What is the earliest example of time travel in literature? A: While H.G. Wells popularized the machine in 1895, the concept appears in the Hindu Mahabharata (circa 400 BCE) with the story of King Kakudmi, who experiences severe time dilation while visiting the creator god Brahma. Another early example is the Japanese folktale Urashima Tarō (8th century), involving relativity-like time slippage in an undersea realm.

Q: What is the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle in fantasy? A: It is a rule stating that in a time-travel scenario, the past cannot be altered. Any action taken by a time traveler in the past was always part of history. This creates a “closed loop,” as seen in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, where Harry realizes he saved himself.

Q: How does Balefire work in The Wheel of Time? A: Balefire is a weave that burns a thread out of the Pattern of Ages. It does not just kill the target; it erases them from existence retroactive to a point in the past. Actions the target took shortly before being hit (like killing someone) are undone. This threatens the stability of the universe (The Pattern).

Q: Why do time travelers in Outlander need gemstones? A: In Diana Gabaldon’s lore, gemstones act as a focus or capacitor to guide the traveler through the chaotic energy of the standing stones. Without them, the traveler risks being torn apart or landing in the wrong time. The gems often shatter or disappear after passage, acting as a “fuel.”

Q: What is the “Grandfather Paradox”? A: The Grandfather Paradox is a logical contradiction where a time traveler goes back and kills their own grandfather before their parent is conceived. If they do this, they are never born, so they cannot travel back to kill the grandfather. Fantasy solves this via Multiverse theories (creating a new timeline) or Fixed Loops (the gun jams/you fail).

Sources

References & Further Reading

- [1] Reddit. (n.d.). Kakudmi, Revati, and the mythical lesson of time.

- [2] Bokksu. (n.d.). Urashima Taro: The Timeless Tale of a Japanese Fisherman.

- [3] Bard Mythologies. (n.d.). Oisín in Tír na nÓg.

- [4] Haimoto-Rudd, A. (2023). A Brief History of Time Travel.

- [5] Screen Rant. (n.d.). Outlander Time Travel Explained: Stones, Gems, and Blood.

- [6] Dragonmount. (n.d.). Wheel of Time: Balefire Mechanics and Origins.

- [7] ThoughtCo. (n.d.). Definition of Closed Timelike Curve.

- [8] AAU. (n.d.). Holiday Science: Scrooge’s Time Travel and Relativity.

- [9] Goodreads. (n.d.). Quotes from Terry Pratchett’s Night Watch.

- [10] Pocket Bard. (n.d.). The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus Legend.

- [11] Origin of Science. (n.d.). Temporal Relativity in Vedic Literature.

- [12] Wizarding World. (n.d.). J.K. Rowling on Time-Turners.

- [13] Medium. (n.d.). Hinduism on Time Travel: The Story of Kakudmi.

- [14] Wikipedia. (n.d.). Urashima Tarō: Folklore and Variations.

- [15] Blarney Stone. (n.d.). Tír na nÓg: The Story of Niamh and Oisín.

- [16] Wilderness Ireland. (n.d.). Legends of Ireland: Niamh Cinn Oir.

- [17] Wikipedia. (n.d.). Seven Sleepers.

- [18] Philmont Scout Ranch. (n.d.). The Enchanted Moccasins and Other Native American Legends.

- [19] World of Tales. (n.d.). Native American Folktales: The Enchanted Moccasins.

- [20] AbeBooks. (n.d.). Memoirs of the Twentieth Century by Samuel Madden.

- [21] Wikipedia. (n.d.). Memoirs of the Twentieth Century Analysis.

- [22] Crooked Timber. (n.d.). Christmas and Time Travel: Into the Scroogiverse.

- [23] Mind Matters. (n.d.). Time Travel in Science Fiction: Examples that Work.

- [24] Wikipedia. (n.d.). A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.

- [25] Reddit. (n.d.). Is time travel intertwined with Isekai?.

- [26] StackExchange. (n.d.). Novikov Self-Consistency Principle.

- [27] Medium. (n.d.). Harry Potter: Is the Time Turner a Problem?.

- [28] Reddit. (n.d.). Meaning of the Inscription on Hermione’s Time-Turner.

- [29] Semester Sequestered. (n.d.). Time Turner Inscription Text.

- [30] Wizarding World. (n.d.). Time-Turner Mechanics and Limitations.

- [31] StackExchange. (n.d.). How does Claire travel through the standing stones?.

- [32] Outlander Watch. (n.d.). The Buzzing of the Stones.

- [33] YouTube. (n.d.). Outlander Time Travel Explained.

- [34] Reddit. (n.d.). What are the rules for time travel in Outlander?.

- [35] Reddit. (n.d.). Causality Question: Balefire.